Everything you wanted to know about “Frozen Peas”, but were afraid to ask

/An abridged version of this piece ran on Wellesnet,

Anyone interested in Orson Welles’ work has sooner or later chuckled along at ‘Frozen Peas’, the notorious out-take in which the actor-director tetchily took to task his director and sound engineer, whilst recording a series of commercials for Findus Frozen Foods. But what was the full story behind it?

Background

Findus are a Scandinavian food company, founded in 1905 and best known for the frozen foods they began selling from 1945. They were a long-term client of the London office of the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency – BFI records indicate that JWT first produced adverts for Findus as early as 1960, and continued doing so until 1980. Welles was only the latest in a string of 1960s celebrity spokespersons for the ads – as late as 1968, TV game show host Michael Miles was used as a narrator, and TV character Alf Garnett had fronted another Findus advert the year before.

Jonathan Lynn has already shed some light on the background of Welles’ association with Findus, and how the working relationship got off to a rocky start. Back in 2016, he allowed me to share with Wellesnet a preview from his memoirs, including:

One night he told us about his voice over for Findus frozen peas. “An ad agency called and asked me to do a voice over. I said I would. Then they said would I please come in and audition. ‘Audition?’ I said. ‘Surely to God there’s someone in your little agency who knows what my voice sounds like?’ Well, they said they knew my voice but it was for the client. So I went in. I wanted the money, I was trying to finish Chimes At Midnight [sic – Lynn may well have been mistaken about the exact project]. I auditioned and they offered me the part! Well, they asked me to go to some little basement studio in Wardour Street to record it. I demanded payment in advance. After I’d gotten the cheque I told them ‘I can’t come to Wardour Street next week, I have to be in Paris.’ I told them to bring their little tape-recorder and meet me at the Georges Cinq Hotel next Wednesday at eleven am. So they flew over to Paris, came to the hotel at eleven – and were told that I had checked out the day before.” He chortled happily. “I left them a message telling them to call me at the Gritti Palace in Venice. They did, and I told them to meet me there on Friday. When they got there I was gone – they found a message telling them to come to Vienna.” Now he was laughing uproariously. “I made them chase me all around Europe with their shitty little tape recorder for ten days. They were sorry they made me audition.”

Archives

I managed to trace the papers of the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency, which are held by Britain’s History of Advertising Trust. They very graciously shared copies of the original production papers for the adverts, including scripts. They offer several interesting insights.

Much as Lynn’s anecdote of a Wellesian chase around Europe tells us a lot about the strained agency relationship from the beginning, it does not mean that the adverts were recorded on a tape recorder in a Vienna hotel or anywhere else on the continent, as has been speculated. They were clearly recorded in a London studio, fully equipped to screen the visual elements identified – probably the “little basement studio in Wardour Street” in London’s Soho district, then still the centre of the production offices for London’s film industry, as well as being the capital’s centuries-old red light district. Indeed, the building was very likely the Pathé Studios at 103-109 Wardour Street, which was a functioning studio for hire from 1910-70, and hosted a myriad of recording sessions for different media. By 1970, the building was shabby, with closure looming.

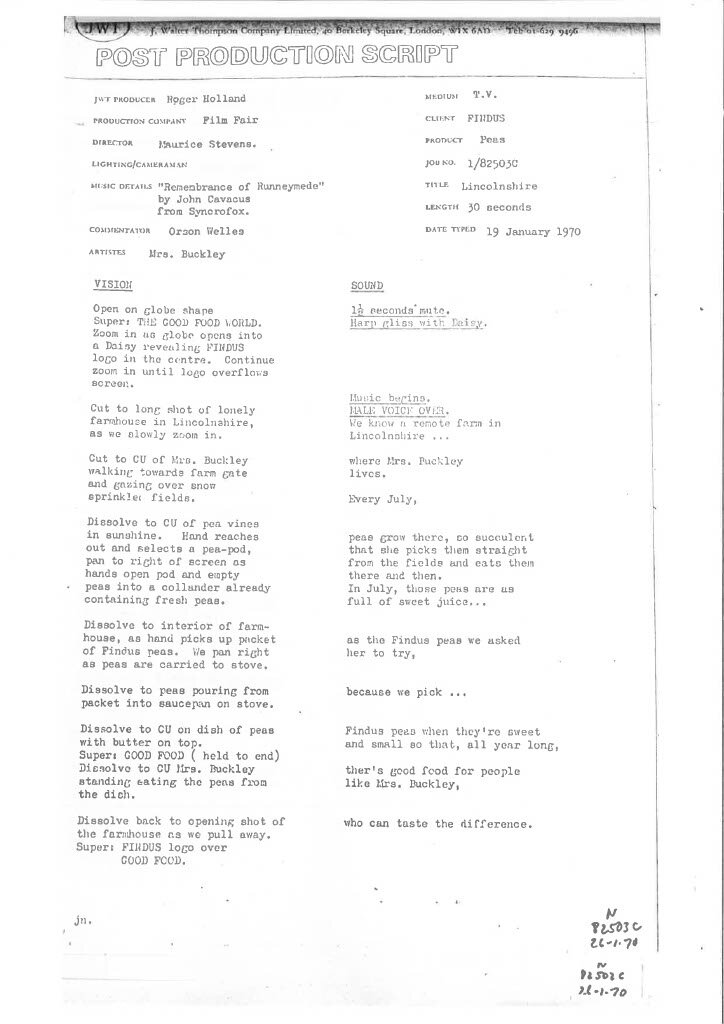

What survives in the J. Walter Thompson archives are post-production scripts, matching Welles’ changes to the copy. Each script typically carries two dates: the first is a “date typed”, which can be taken as having been soon after the original recording session, probably within a week. The second is a handwritten footer note in the margin with a production number matching BFI records, and a date a week or two later. I believe this latter date to refer to when the final cut of the fully narrated advert was edited and synced, the production number referring to the final product.

Thus the “Lincolnshire” segment of “Frozen Peas” was typed up on 19 January 1970. Intriguingly, this advert alone had two handwritten dates with serial numbers, covering 26 and 28 January 1970. Given a combination of Welles’ tetchiness in recording, and the mammoth nature of the recording (more on that later), I would suggest that this points to two attempts at edits of the final ad.

That the post-production scripts reflect Welles’s final delivery is confirmed by comparing the post-production scripts with Welles in the out-takes – although it is noticeable that the phrase “crumb crisp coating”, which apparently caused Welles so much annoyance, did appear.

Another detail emerges from the papers. Most of Welles’s Findus ads were farmed out by the agency to the production company Les Films Pierre Remont, with a director credited as “Monsieur Dimka”. A 1959 listing in the trade paper Business Screen Magazine shows Les Films Pierre Remont to be based in Paris’ affluent 8eme arrondisement, a company dating to 1949, with Dimka cited as a co-producer and director. The company specialised in filming adverts, and its clients already included the J. Walter Thompson agency. Dimitri Dimka certainly moved in similar circles to Welles – he had been a cinematographer on a 1959 documentary short by Montenegrin director Frédéric Rossif, who went on to co-direct with François Reichenbach the flattering 1968 ‘Nouvelle Vague’ French documentary Portrait: Orson Welles – one wonders if Rossif affected an introduction. Dimka directed all of Welles’s 1969 adverts for Findus, although one was through a different company, the Geneva-based Listar International, for reasons unknown.

When it came to the fraught January 1970 recording session, the adverts were filmed by a new company, Film Fair, with a young director, Maurice Stevens. Stevens would have been in the business for less time than Dimka – at the time Les Films Pierre Remont was starting up in 1949, Stevens was still studying at Hornsey College of Art. Welles’s obvious displeasure in the recordings was thus likely aggravated by dealing with a new director.

Anyway, given the sheer difficulty of tracing Welles’ nomadic movements around Europe at the time, I present below a table of the dates gleaned from documentation. As previously noted, several of the adverts survive and have been digitised, with links given when the video survives.

Date typed; Prod. No.; Title; Product; Production company; Director; Notes

30 January 1969; 81829; Picking; Peas; Les Films Pierre Remont; Monsieur Dimka; A later copy of the same script is dated 13 February 1969.

27 February 1969; 81831; Sliced Braised Beef; Sliced beef; Les Films Pierre Remont; Monsieur Dimka; Recorded at the same time as the below.

27 February 1969; 81831 (BB); Braised Beef II; Sliced beef; Les Films Pierre Remont; Monsieur Dimka; Variant on the first beef ad – first half was identical. Copy exists dated 25 February 1969.

6 March 1969; 81835C; Fish Portions; Fish portions (cod, haddock, plaice, hake); Les Films Pierre Remont; Monsieur Dimka

6 May 1969; 81830; Fresh Caught; Fish fingers; Listar International; Monsieur Dimka

4 August 1969; 81832; Beefburger; Beefburger; Les Films Pierre Remont; Monsieur Dinka

16 January 1970; 82505C; Norway; Fish fingers; Film Fair; [uncredited]; Source of the “Norway” out-takes.

19 January 1970; 82502C; Far West; Beefburger; Film Fair; [uncredited]; Source of the “Far West” out-takes.

19 January 1970; 82502C and 82503C; Lincolnshire; Peas; Film Fair; Maurice Stevens; Source of the “Lincolnshire” out-takes.

January? 1970; Not known; France; Not known; Not known; Not known

January? 1970; Not known; Highlands; Sliced beef ;Not known; Not known

January? 1970;Not known; Normandy; Not known; Not known; Not known

January? 1970; Not known; Shetland; Fish portions; Not known; Not known

January? 1970; Not known; Sweden; Cod portions; Not known; Not known

The documentation also bears out the director’s comment in the out-take, shortly before Welles walks out at the end, “Orson, you did six [commercials for us] last year”.

Two credits remained constant throughout the paperwork: J. Walter Thompson producer Roger Holland, and lighting/cinematographer Bob Zubouwitch, although the latter need not have ever met Welles, since Welles was only providing voiceovers to pre-filmed footage.

Real people?

Lincolnshire’s “Mrs. Buckley”, Norway’s “Jon Stangeland” and the American West’s “Charlie Briggs” are listed as “artistes” in paperwork discussing visual advert elements of them, suggesting that they may have been real people rather than actors.

The format of the adverts made it clear that real people were being captured, typically farmers and fishermen, and surviving clips seem to support this. I have been able to ascertain that the Buckleys of Lincolnshire are a long-standing agricultural family, and indeed that they still grow peas there today!

When was ‘Frozen Peas’ recorded?

Given that documentary evidence survives for both ‘Braised Beef’ segments in February 1969 having been recorded at the same time, but that post-production scripts were also typed up two days apart, it is likely that the whole ‘Frozen Peas’ segment was all from the same recording session, even though the transcriptions are dated three days apart. Crucially, 16 January 1970 was a Friday, and 19 January 1970 was a Monday, suggesting that some of the transcription work was simply left to do after the weekend. It is therefore overwhelmingly likely that ‘Frozen Peas’ was recorded sometime in the week up to and including 15 January 1970.

Original post-production script for the ‘Lincolnshire‘ segment of ‘Frozen Peas’. Courtesy of the J Walter Thompson archive at the History of Advertising Trust (HAT).

It appears that the surviving J. Walter Thompson scripts are not exhaustive, though. Comparing them to the BFI’s records and the surviving footages, whilst there is some duplication with the production paperwork, one finds BFI listings for five more 1970 Findus adverts made, but not included in the above: “France”, “Highlands”, “Normandy”, “Shetland” and “Sweden”. Recordings of several of these survive. Whereas the 1969 adverts were in black-and-white, the 1970 ones were in colour. From the jump in production codes for the January 1970 recording session (82502C, 82503C, 82505C) it is likely that at least one of these adverts was the “missing” 82504C; and indeed quite probable that all eight commercials were recorded together, back-to-back, in one mammoth recording session. This is doubly likely, as their voiceovers all follow the same structure – introducing a locale, with a person, discussing the Findus product, and finishing on “people like [name of person], who can taste the difference.”

Findus advertising after Welles

Findus had already been moving between spokespersons before Welles. After the 1970 advert session, it is perhaps unsurprising that they did not renew his contract, and reverted to rotating narrators. A 1972 commercial with English comedian Sam Kelly is so dated with its obnoxious materialism and casual sexism, it looks uncannily like the spoof advert in Michael Winner’s 1967 film I’ll Never Forget Whatsisname – which coincidentally featured Welles as the jaded, unscrupulous advertising executive producing such tripe. By 1974, Findus had a longer-term narrator for a series of adverts, in the dulcet Scottish tones of actor Gordon Jackson, by then best known for his starring role in Upstairs, Downstairs. Two decades earlier, Jackson had worked for Welles, in the London stage production of the experimental Moby Dick, Rehearsed.

Where do the Findus adverts fit in to Welles’ career?

At the time of these adverts, Welles was living with his wife and youngest daughter at the Mori family villa in Fregene, outside Rome, although he continued working all over Europe. He had three major projects underway, which the ‘Frozen Peas’ commercial was helping to fund. With so many overlapping strands in Welles’ life, it is important to understand why he took on this particular advertising work.

The first two projects were The Deep, a thriller filmed periodically on boats over summers in Yugoslavia in 1967-9 as climate permitted, and Orson’s Bag, containing a series of sketches and a half-hour condensation of The Merchant of Venice. By 1969, the original funding for Orson’s Bag as a CBS American TV special had dried up, over disagreements on whether his Luxembourg-based holding company could be paid by CBS, but he continued to work on the segments out of his own resources. As late as 1971, he was still filming the linking narration in London. The Merchant of Venice in particular consumed much of his time on the editing at Safa Palatino Studios, a version being completed in 1969, prior to the loss of several key film elements. Both The Deep and Orson’s Bag were major projects he shared with his long-term lover, Oja Kodar.

The third major project Welles was engaged in was his long-standing Don Quixote. While the project had been conceived in various forms since the mid-1950s, most of the filming was done in Italy in 1959-64, and by 1964 a fully-edited workprint existed, Don Quixote Goes to the Moon, named after its ending. Welles held on to this edit through the 1960s (it was shown to his friend Juan Cobos around 1965, essentially completed), mindful that the avowedly non-commercial film could harm his career, and that he first needed a major commercial success to pave the way for something as idiosyncratic. After a disappointing box office response to Chimes at Midnight (1966), it appears he had his hopes pinned on first The Deep (1967-9) and then The Other Side of the Wind (1970 onwards) as the “commercial” movie that would pave the way for Don Quixote. But the project suffered a further, self-inflicted setback in 1969: Welles binned most of his own workprint, believing that the July 1969 moon landings “ruined it.” What had seemed magical five years earlier was now passé. Welles thus began extensive further tinkering on Don Quixote, which would remain unfinished for the rest of his life.

Of this period, Jean-Pierre Berthomé and Francois Thomas write in Orson Welles at Work (2006, trans, 2008):

In 1970, with The Deep, Orson’s Bag and also Don Quixote, Welles found himself with three pieces of work on which filming was more or less complete, but which he could not finish for lack of money. The negatives and positives were scattered in different places while continuity demanded the filming of shots in which the actors were present.

This adds some much-needed context on Welles’s exasperation whilst doing a lucrative but intellectually “unrewarding” commercial voiceover.

A long-standing story from several Welles biographies is that he was outraged by an Italian tabloid covering his extra-marital relationship with Oja Kodar, and left Italy in a rage, drawing an abrupt close on the productive European phase of Welles’s career (1947-56 & 1957-70). Beatrice Welles’ confirmation that she and her mother did not know of Kodar’s existence until 1984 strongly suggests that he was also keen to leave the country to keep Kodar’s existence from them. The Welles family first moved to London for a few months of 1970, and then to the USA. Thanks to Alberto Anile’s scholarly Orson Welles in Italy (2006, trans. 2013), we can trace his departure to February 1970, from the date of the offending article (‘Welles enjoys Oja’s company in his wife’s absence’, Oggi, 17 February 1970). Thus ‘Frozen Peas’ was recorded just a month prior to this major upheaval in Welles’ life on several levels (not least the rushed departure which saw all the reels of Don Quixote negative left behind). The move to London was temporary, though no doubt a productive one, as it afforded the opportunity to do more filming on Orson’s Bag, as well as several well-remunerated talk show appearances with David Frost. By July 1970, Welles was renting a cottage in the Beverly Hills Hotel in Los Angeles, and he started filming The Other Side of the Wind the following month. Thus the Findus commercials were at the very tail-end of his long European sojourn, without any sense yet that his decades of being mainly based in Europe would soon be coming to a close.

Swinging London

Looking at Welles’s production schedule around this time, it seems highly likely the 1969 Findus recording dates in London would have been at the same time as he was filming the first ‘Swinging London’ scenes of Orson’s Bag, centred around Carnaby Street.

As noted above, the Findus commercials were recorded in Soho’s Wardour Street, a short walk from Soho’s Carnaby Street. Glimpses of the area can be found in ‘Swinging London’, including the strip-tease clubs which marked the area. These scenes were shot sometime between November 1968 and February 1969 – something I was able to confirm with the late Tim Brooke-Taylor, who in 2016 sent me his recollection of working with Welles. (Much of the material he sent me is reproduced in this 2017 interview here.)

Welles had first seen him and Graeme Garden in a (now mostly lost) TV comedy series called Broaden Your Mind, the first episode of which aired on BBC2 on 28 October 1968. Brooke-Taylor recalled that he and Garden were “nervously watching the first episode” together:

As the show finished the phone rang in Graeme’s flat. Graeme talked for a while, put the phone down and said, “That was Orson Welles.”

“Funny you should say that”, I said, “I was expecting a call from the Pope.”

“No, it really was him.”

“Really?”

“Yes, really.”

The series does not seem to have been sold abroad, so Welles would have needed to be staying in the UK to watch the broadcasts. Brooke-Taylor clarified that Welles admired the zany, madcap, Pythonesque humour that he and Garden wrote (both were university contemporaries of future Monty Python writer-performers Graham Chapman, John Cleese and Eric Idle, with all of them being active in Cambridge’s Footlights troupe). Welles therefore asked Brooke-Taylor and Garden to write as well as perform in several of the ‘Swinging London’ scenes, including the ‘Carnaby Street’ and ‘Aristocrats’ sketches (Brooke-Taylor told me he remembered writing the latter). Garden also contributed narration to the ‘Churchill’ segment. These scenes were shot before the February 1969 Rome shoot on The Thirteen Chairs (where Welles and Brooke-Taylor co-starred), tallying with the January 1969 recording dates of Welles’s first Findus commercials, and most likely being shot back-to-back with the ads, on his trips from Rome to London.

Intriguingly, while Brooke-Taylor and Garden would achieve fame as a trio from 1970, along with their Cambridge Footlights contemporary Bill Oddie, and while Oddie was attached to the ‘Swinging London’ project, they were not all working on it at the same time. Brooke-Taylor recalled, “I don’t remember the ‘one-man band’ being part of it, though we certainly knew it as one of Bill Oddie’s songs.” When I asked Bill Oddie of his recollection of it, he told me:

This is one of those lost events. I didn’t work with Orson Welles and I never met him. I was aware that Tim and Graeme did something, but I have no knowledge of [the song] One Man Band being incorporated. I wrote that for radio ISRTA [for I’m Sorry, I’ll Read That Again, 1964-73], and as far as I recall it went no further.

It therefore seems likely that the ‘One Man Band’ sequence was a belated addition by Welles (with or without Oddie’s knowledge), shot later than the other scenes, and edited into it. Those additional scenes were clearly filmed before the summer of 1970 (when Welles grew a beard), but sometime after Brooke-Taylor and Garden completed their scenes in February 1969, so could quite plausibly have been shot around the time of the ‘Frozen Peas’ out-takes in January 1970. However, studying Welles’s performances synchronised to the music, as a one-man-band, a policeman, a street sweeper, an angry old woman, a Chinese strip-tease promoter, and a flower woman selling “dirty postcards”, none of these scenes show any evidence of having been filmed in London (unlike the reverse-angle shots with Brooke-Taylor). They could just as easily have been filmed in Italy, France or Yugoslavia. Welles was therefore juggling these reinventions of the material all through ‘Frozen Peas’, whilst he was yet to film the linking narration until 1971, when he was in London filming links for the Marty Feldman Comedy Machine.

Reputation

I recently spoke to Peter Shillingford, assistant director on several of the Paul Masson adverts, (including Welles’ other well-known out-take), and I was intrigued by an observation he made. Apparently, by the late 1970s, Welles bemoaned that he was having much more difficulty getting voiceover work.

Shillingford had three lunches with Welles at his favourite Los Angeles restaurant Ma Maison in 1979 – before and after the well-known out-take – and what prompted them was Shillingford’s offer to help him secure more voiceover work. During the first lunch, it emerged that Welles had heard of the existence of a bootleg recording of him in circulation, reinforcing his ‘difficult’ image, but had not heard it himself. Shillingford had access to a copy, and played it to him on a tape recorder over a subsequent lunch in Ma Maison, the two of them laughing along.

It appears that Shillingford’s efforts were not in vain – Welles’ credits in 1980 show a significant rise in the amount of voiceover work Welles undertook compared to the late 1970s. Nonetheless, the ‘Frozen Peas’ bootleg tape continued to have a life of its own.

[FOOTNOTE: Brooke-Taylor’s recollection of nervously watching Broaden Your Mind with Graeme Garden was that it was of the first episode of the second season, but that is not possible: that didn’t air until November 1969, seven months after The Thirteen Chairs was filmed – Brooke-Taylor was adamant in correcting my assumption that The Thirteen Chairs came first, saying that they first met Welles when making ‘Swinging London’, so it would have had to be the first series in 1968 for that to have worked. That is also consistent with the non-participation of Bill Oddie – Oddie played no role in season one of Broaden Your Mind, but joined the cast in season two.]