Cumberland House, 85-87 Pall Mall, 1765-1908; by 1888 it was interconnected with a network of surrounding buildings (note the house on the far-left, one of the candidates for Mycroft’s lodgings). Courtesy of the Victorian London website, http://www.victorianlondon.org/organisations/waroffice.htm.

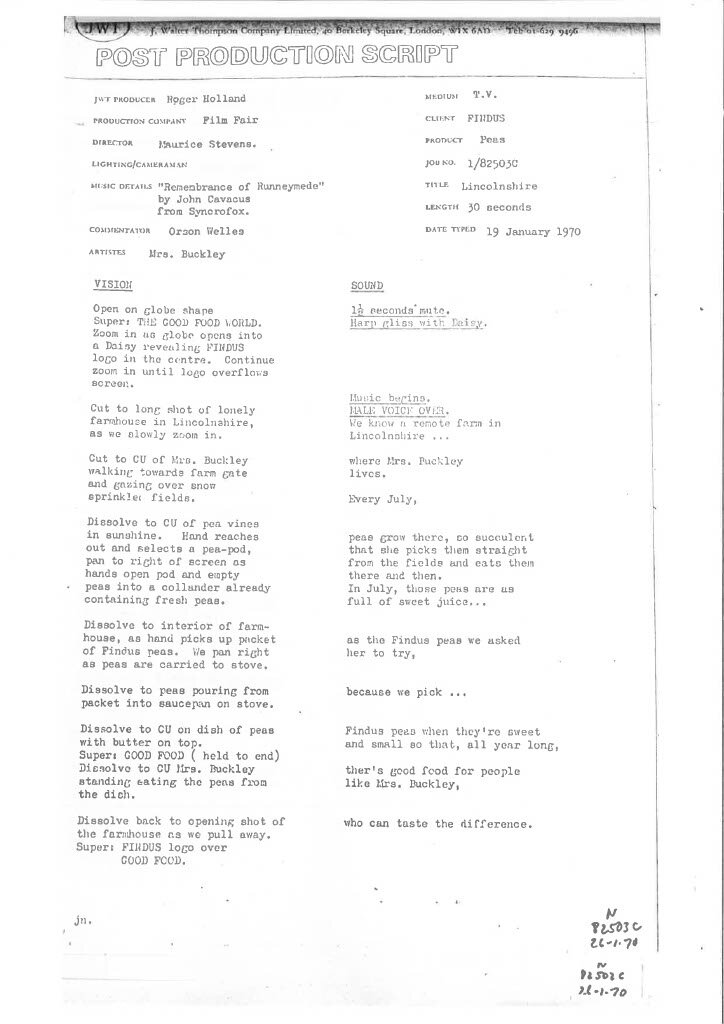

If we take the Junior Carlton Club to be the Diogenes, then the obvious candidate is the gargantuan Ordnance Office and War Office building directly opposite. Cumberland House, a late-Palladian mansion, stood at 85-87 Pall Mall, on the south side of the street. From 1806 until its demolition in 1908, it served as the Ordnance Office; and from 1858, it housed the War Office as well. The building’s layout was a complex one, embedding a rag-bag of neighbouring houses and buildings, and knocking them through into a tangled web of “thirteen rambling buildings”.[76] Two buildings, east of Cumberland House, were on Pall Mall, directly in front of the Junior Carlton Club. These houses had been residential in design, and so it is not inconceivable that this much-derided rag-bag of buildings would have included some government-owned apartments. We know that Mycroft worked in Whitehall, not Pall Mall; but the Ordnance Office, which was tasked with the requisition of munitions and military supplies, would doubtless have required skilled auditors such as Mycroft, and so it is quite conceivable that he acquired the use of some government-owned apartment under the Office’s aegis, in exchange for occasional services. This ongoing Ordnance Office connection would also offer some insight into Mycroft’s keen interest in the development of the Bruce-Partington submarine, from its earliest stages of planning.[77]

A further circumstantial piece of evidence can be found in the two individuals whom the Holmes brothers sighted from the Club’s bow window overlooking Pall Mall, one a billiard-marker, the other an elderly Non-Commissioned Officer, who had only recently been discharged after serving some years in India. The billiard-marker could have easily come from almost any club in Pall Mall. But the soldier would have been less easy to place. None of the Pall Mall military clubs admitted NCOs – they were all strictly officers-only. The War Office building opposite the Junior Carlton, on the other hand, offers an obvious point from which this soldier would have been coming or going.[78] Mycroft’s additional observations that the man was widowed with two children could have made it quite plausible that the recently-discharged soldier was enquiring about his pension.

There is another possibility, which supports the Athenaeum, Travellers and Reform Clubs. To the rear of the south side of Pall Mall runs Carlton House Terrace, made up of twenty houses constructed on the grounds of the old Carlton House. Numbers 3-9 Carlton House Terrace directly face the back of these three clubs on the south side of Pall Mall, with only the Clubs’ rear gardens between them. The street’s prestigious John Nash-designed villas were mainly residential in the late nineteenth century, with a succession of rich and influential occupants, including three current or future Prime Ministers; plus the Foreign Secretary’s official residence in Carlton Gardens, a small cul-de-sac at the end of the terrace. (The Duke of Holderness in ‘The Priory School’ also resides there.) Professor Leal argues that “Mycroft may not be rich, [but] he is not poor”, citing his £450 annual salary as $60,000 in today’s money.[79] Even with such income, it is inconceivable that Mycroft could have afforded lodgings on one of London’s premier streets, without considerable financial assistance.

With so many of these buildings having been in the hands of significant government figures, it is not too great a leap to see how and why a man in Mycroft’s position might have been offered free or subsidised lodgings by the government. This is particularly plausible if one considers that Number 3 was occupied by MI6, Britain’s intelligence service with roots going back to at least 1909.[80] Relatively little is known about the tenure of their occupancy – a residency for at least two decades after World War II has been confirmed, but it is unclear how long they had been there for, or how long they remained. An obvious incentive for maintaining a British intelligence presence on the street would have been the location of the German Embassy at Number 9 from 1849 until 1939 (with an interregnum from 1914-1919, for self-evident reasons) – a point referenced in ‘His Last Bow’, as “things are moving at present in Carlton Terrace”.[81]

It is therefore easily tenable that if the Diogenes were based on the Athenaeum, Reform or Travellers Clubs, Mycroft could have resided on Carlton House Terrace opposite.

Conclusion

It is unlikely that the Diogenes Club was a pseudonym for the Travellers or Reform Clubs. Mycroft’s deep reluctance to travel made him unlikely to have ever qualified for Travellers Club membership, while none of the grounds advanced by Professor Leal for the Reform Club bear up under sustained scrutiny.

The most likely conclusion, of course, is that the Diogenes Club was a composite – a figment of Watson’s febrile imagination, embodying both affection and satire for the oddities of London’s Clubland. Two stories established that Watson was a clubman himself, and Holmes once referred to how “You returned from the club last night”, though the only clues offered to its identity were that it had billiards tables that Watson seldom used, and his non-familiarity with the Diogenes Club means he probably did not frequent that section of Pall Mall.[82] It is therefore likely that his gentle mockery of the Diogenes pointed to affection rather than disenchantment with Clubland. This conclusion certainly offers the most leeway for creativity, and is to be embraced by all who delight in the many pastiche adventures of the Diogenes Club.

Yet it is also plausible that it was merely a pseudonym for a real club, as was the case with much of Watson’s storytelling. In weighing up so many of the “usual suspects” – the Athenaeum, the Travellers, the Reform, and the Marlborough – our personal conclusions come down to how much we suspect Watson of engaging in willful misdirection. If this is the case, then the Athenaeum and Marlborough Clubs deserve recognition as likely candidates. The problem with this approach is that it depends on willfully ignoring some evidence, and selectively picking which evidence supports each club. If we are to look at the totality of the evidence, and to take all of Watson’s narrative at face value, then we are inexorably drawn towards one conclusion: only the Junior Carlton Club matches the Diogenes Club’s full description.

Dr Seth Alexander Thévoz is the author of Club Government: How the Early Victorian World was Ruled from London Clubs (London: I. B. Tauris, 2018). He is Honorary Librarian of the National Liberal Club.

FOOTNOTES

[1] I should like to thank Kayleigh Betterton of Birkbeck College, University of London, and Dr Tim Oliver of Loughborough University London, for their constructive comments after seeing a draft of this article. I am also grateful to Christopher Raper for highlighting an innacuracy in an earlier version of this article, about the internal layout of the Travellers Club at the time, which has since been corrected.

[2] David L. Leal, ‘What was the Diogenes Club?’, Baker Street Journal, 67:2 (Summer, 2017), pp. 16-26.

[3] There was already considerable interest in the Club by the 1960s – see Charles O. Merriman, 'In Clubland', Sherlock Holmes Journal, 7:1 (Winter, 1964), pp. 29-30; S. Tupper Bigelow 'Identifying the Diogenes Club: An Armchair Exercise', Baker Street Journal, 18:2 (June, 1968), pp. 67-73.

[4] Leslie S. Klinger (ed.), The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, Vol. I (New York: Norton, 2004), pp. 640-641.

[5] Quoted in William S. Baring-Gould (ed.), The Annotated Sherlock Holmes, Vol. I, (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1967), p. 591.

[6] ‘The Hound of the Baskervilles’ (1902).

[7] Michael Havers, Edward Grayson and Peter Shankland, The Royal Baccarat Scandal (London: Souvenir Press, 1977).

[8] Review of Charles Graves, Leather Armchairs: The Chivas Regal Book of Clubs (London: Collins, 1963); in Orville Prescott, ‘Books of the The Times’, New York Times, 30 November 1964; quoted in ‘Letters’, Baker Street Journal, 15:2 (June 1965), p. 126, and ‘Letters’, Baker Street Journal, 18:3 (September 1968), pp. 183, 186.

[9] Bigelow, ‘Diogenes’ (1968), pp. 67-73.

[10] David Marcum, ‘Pall Mall: Locating the Diogenes Club’, Baker Street Journal, 67:2 (Summer, 2017), pp. 27-33.

[11] John Thole, The Oxford and Cambridge Clubs in London (London: Oxford and Cambridge Club/Alfred Waller, 1992), pp. 97-8.

[12] ‘Pall Mall, North Side, Existing Buildings’, in F. H. W. Sheppard (ed.), Survey of London: Volume 29, St. James’s and Westminster, Part 1 (London: HMSO, 1960), p. 343.

[13] Leal, ‘Diogenes' (2017), p. 20. This point is also made in Klinger (ed.), Annotated Sherlock Holmes, I (2004), p. 640.

[14] Ibid., p. 16.

[15] ‘The Greek Interpreter’ (1893).

[16] Leal, ‘Diogenes' (2017), p. 22; Merriman, 'Clubland’ (1964), pp. 29-30.

[17] P. G. Wodehouse, The Adventures of Sally (London: Everyman, 2011 [first pub. 2011]), p. 101 ; P. G. Wodehouse, ‘Archibald and the Masses’, in P. G. Wodehouse, Young Men in Spats (London: Everyman, 2002 [first pub. 1936]), p. 202. ; P. G. Wodehouse, ‘All’s Well with Bingo’, in P. G. Wodehouse, Eggs, Beans and Crumpets (London: Everyman, 2000 [first pub. 1940]), p. 12.

[18] Sophie Ratcliffe (ed.), P. G. Wodehouse: A Life in Letters (New York: W. W. Norton, 2013), p. 64, 1n.

[19] Leal, ‘Diogenes' (2017), p. 23.

[20] The National Liberal Club subsequently had an even more extensive library than the Athenaeum, but even though its clubhouse had opened in 1887, its Gladstone Library would not formally open until 1892, making it implausible as a serious candidate for the 1888 events of ‘The Greek Interpreter’, where Mycroft’s routine is well-established.

[21] Leal, ‘Diogenes' (2017), p. 17.

[22] Bigelow, ‘Diogenes’ (1968), p. 70.

[23] Thévoz, Club Government (2018), pp. 131-139.

[24] Sheppard (ed.), Survey of London: 29 (1960), p. 344.

[25] Klinger (ed.), Annotated Sherlock Holmes, I (2004), p. 641.

[26] Leal, ‘Diogenes' (2017), p. 16, 22.

[27] Ralph Nevill, London Clubs: Their History and Treasures (London: Chatto and Windus, 1912), pp. 279-282

[28] Quoted in William S. Baring-Gould (ed.), The Annotated Sherlock Holmes, Vol. I, (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1967), p. 591.

[29] Thévoz, Club Government (2018), p. 240.

[30] Ibid., p. 46.

[31] Mordaunt Crook, ‘Blackballing’, in Fernández-Armesto (ed.), Armchair Athenians (2001), pp. 19-30

[32] ‘The Greek Interpreter’ (1893).

[33] Ibid.

[34] White’s, for instance, had no library, and a number of its members saw this as a source of pride. Thévoz, Club Government (2018), p. 149. See also the extended discussion of Clubland newspapers in Stephen Koss, The Rise and Fall of the Political Press in Britain: Volume I – The Nineteenth Century (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1981).

[35] ‘The Greek Interpreter’ (1893).

[36] Seth Alexander Thévoz, Club Government: How the Early Victorian World was Ruled from London Clubs (London: I. B. Tauris, 2018), pp. 22-23.

[37] Leal, ‘Diogenes' (2017), p. 23.

[38] Barry Phelps, Power and the Party: A History of the Carlton Club, 1832-1982 (London, Macmillan, 1982), pp. 34-36.

[39] Thévoz, Club Government (2018), pp. 82-93.

[40] Ibid., pp. 82-93; J. Mordaunt Crook, ‘Locked Out of Paradise: Blackballing at the Athenaeum, 1824-1935’, in Felipe Fernández-Armesto (ed.), Armchair Athenians: Essays from the Athenaeum (London: Athenaeum, 2001), pp. 19-30; Amy Milne-Smith, London Clubland: A Cultural History of Gender and Class in Late-Victorian Britain (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 35-57.

[41] Thévoz, Club Government (2018), pp. 90-92.

[42] Rod Barron, ‘Politics Personified: Fred W. Rose and Liberal & Tory Serio-Comic Maps, 1877-1880 – Part 1’, Barron Maps blog, 11 March 2016, http://www.barronmaps.com/politics-personified-fred-w-rose-and-serio-comic-maps-1877-1880-part-1/.

[43] Examples include the Devonshire Club founded in 1874 (provisionally called the Junior Reform Club before its launch), and “the New University Club…was founded, in 1864, to accommodate those awaiting election at the older clubs.” Thole, Oxford and Cambridge Clubs (1992), p. 25. Both were on St. James’s Street.

[44] Seth Alexander Thévoz, ‘Club Government’, History Today, 63:2 (February, 2013), pp. 58-59.

[45] Quoted in William S. Baring-Gould (ed.), The Annotated Sherlock Holmes, Vol. I, (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1967), p. 593.

[46] William S. Baring-Gould, Sherlock Holmes: A Biography of the World’s First Consulting Detective (London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1962), p. 16.

[47] Ibid., pp. 11-17.

[48] F. H. W. Sheppard (ed.), Survey of London: Volume 29, St. James’s and Westminster, Part 1 (London: HMSO, 1960), p. 341.

[49] ‘The Greek Interpreter’ (1893).

[50] Ibid.

[51] Thévoz, Club Government (2018), pp. 143-147.

[52] Ibid., p. 144.

[53] William D. Jenkins, ‘The Adventure of the Misplaced Armchair’, Baker Street Journal, 19:1 (March, 1969), pp. 12-16.

[54] Ibid., p. 91.

[55] Seth Alexander Thévoz, ‘Database of MPs’ club memberships, 1832-68’, www.sethalexanderthevoz.com/database-mps-clubs/.

[56] To reach this conclusion, one need only look at the catalogue of members’ disputes which punctuate MS ‘Junior Carlton Club General Meeting Minutes, Volume 1, 1865–1967’, Junior Carlton Club archive, London Metropolitan Archive.

[57] Charles Graves, Leather Armchairs: The Chivas Regal Book of Clubs (London: Cassell, 1963), p. 96.

[58] A phrase which evolved in the 1820s, in the run-up to the Reform Act which gives its name to the Reform Club. E. A. Smith, Lord Grey, 1764-1845 (London: Alan Sutton, 1996), p. 279.

[59] Leal, ‘Diogenes' (2017), p. 17.

[60] Ibid., p. 19.

[61] ‘The Greek Interpreter’ (1893).

[62] Plans of the Junior Carlton Club (1935), embedding the 1885-6 rebuild of the clubhouse, Junior Carlton Club archive, London Metropolitan Archive.

[63] ‘The Greek Interpreter’ (1893).

[64] Leal, ‘Diogenes' (2017), p. 17.

[65] See Marcus Binney and David Mann (eds), Boodle’s: Celebrating 250 Years, 1762-2012 (London: Boodle’s/Libanus Press, 2013); Anthony Lejeune, White’s: The First Three Hundred Years (London: A&C Black, 1993).

[66] ‘Plate 120c: Junior Carlton Club, Pall Mall, Ground-floor plan, published 1867’ in, Sheppard (ed.), Survey of London: 29 (1960).

[67] Charles Graves, Leather Armchairs: The Chivas Regal Book of Clubs (London: Cassell, 1963), p. 96.

[68] Charles Petrie and Alistair Cooke, The Carlton Club, 1832-2007 (London: Carlton Club), p. 210.

[69] ‘Plate 120c: Junior Carlton Club, Pall Mall, Ground-floor plan, published 1867’ in, Sheppard (ed.), Survey of London: 29 (1960); Plans of the Junior Carlton Club (1935), embedding the 1885-6 rebuild of the clubhouse, Junior Carlton Club archive, London Metropolitan Archive. A comparison of the 1869 and 1886 floorplans makes it clear how dramatic the expansion was.

[70] Plans of the Junior Carlton Club (1935), embedding the 1885-6 rebuild of the clubhouse, Junior Carlton Club archive, London Metropolitan Archive.

[71] ‘The Greek Interpreter’ (1893).

[72] J. Macvicar Anderson, ‘Junior Carlton Club, 30 Pall Mall, Westminster, Greater London’, taken on 21 March 1888, hosted by the Historic England website, http://viewfinder.english-heritage.org.uk/search/reference.aspx?uid=215925&index=5928&mainQuery=westminster,%20london&searchType=all&form=home.

[73] Plans of the Junior Carlton Club (1935), embedding the 1885-6 rebuild of the clubhouse, Junior Carlton Club archive, London Metropolitan Archive.

[74] ‘The Greek Interpreter’ (1893); ‘The Final Problem’ (1893); ‘The Bruce-Partington Plans’ (1908).

[75] Klinger (ed.), Annotated Sherlock Holmes, I (2004), p. 640.

[76] Piers Brendon, The Motoring Century: The Story of the Royal Automobile Club (London: Bloomsbury, 1997), p. 135.

[77] ‘The Bruce-Partington Plans’ (1908).

[78] I am grateful to Dr Tim Oliver for making this shrewd observation.

[79] Leal, ‘Diogenes' (2017), p. 17.

[80] Stephen Dorril, MI6: Fifty Years of Special Operations (London: Fourth Estate, 2000).

[81] ‘His Last Bow’ (1917).

[82] ‘The Dancing Men’ (1903); ‘The Hound of the Baskervilles’ (1902).